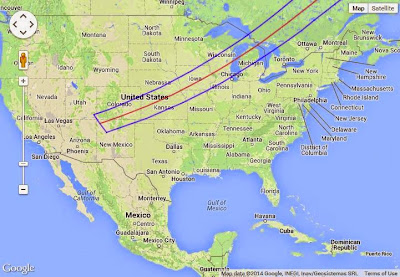

In "Breaking Bad", Season 5a, episode 5, "Dead Freight", Lydia is kidnapped and taken to a hidden basement. To save her life, she describes a railroad radio dead zone by pointing at a map. But there is no railroad at the place where she points. What is at that point?

Whitehorse, just across Chacra Mesa from Pueblo Pintado, the easternmost "gateway" community of Chaco Canyon.

To me, this proximity isn't accidental, but speaks to something deeper. Lydia is pointing at a location on the very edge of the center (but not directly at the center) of Anasazi civilization at Chaco Canyon. But why? What does it mean? Perhaps "Breaking Bad" is making a commentary on Anasazi history and suggesting an analogy to Walt's drug empire.

In "Breaking Bad", the radio silence zone on the railroad is a place where a conspiracy work to steal methylamine, subvert the railroad, and thus subvert modern civilization, without being observed. Whitehorse is an analogous place; a place where ordinary, disaffected inhabitants can gather with little chance of discovery and work at subverting the powers controlling Anasazi civilization.

Whitehorse is very close to, but out of direct visual sight, of Chaco Canyon: outside Steve Lekson's "Downtown Chaco" and surrounding "Chaco Halo" (Fagan, 2005). Imagine the summit of La Fajada Butte at Chaco Canyon as possessing an Eye-of-Sauron-like lighthouse-like beam scanning the horizon. As seen from La Fajada Butte, Whitehorse is just behind Red Mountain, just out of view of the ‘Eye of Sauron’, and is thus a reasonable location from which ordinary people might hatch conspiracies against the central power in adjacent Chaco Canyon.

But then this implies Vince Gilligan and the Breaking Bad team might have opinions and attitudes about not just modern American civilization, but Anasazi civilization too, maybe seeing certain affinities with modern civilization. What might the affinities be between a premodern society and today's world? One might presume Gilligan, et al. would be attracted to the idea of siding with a group of brigands, or better yet, disaffected rebels struggling against an oppressive power, such as might be presumed to rule at Chaco Canyon. Of course, oppressive powers often refer to rebels as brigands.

A certain theatricality was likely central to Anasazi power (Sofaer, 2008):

Scholars have commented extensively on the impractical and enigmatic aspects of the Chacoan buildings, describing them as "overbuilt and overembellished" and proposing that they were built primarily for public image and ritual expression."

Chaco Canyon dominated the "Chaco Basin". It was centrally located, functioning almost as a 'Mecca' of the Pueblo world.

Anasazi spiritual power derived in part from command of astronomical knowledge, whose patterns they embedded in the landscape. Virtually every major Chaco Canyon structure features walls oriented to azimuths of solar or lunar importance (particularly major or minor lunar standstills), and corners aligned with these directions, and were located with respect to one another along these azimuths (Sofaer, et al., 2008). Similarly, modern patterns of economic power - national and international trade - have also been embedded in the landscape, in the form of railroads.

The Whitehorse area contains a number of Anasazi ruins. Nevertheless, there is no indication it contained elements central to Anasazi astronomical observations and political power. It doesn't sit along any notable azimuths with respect to Pueblo Bonito and Chaco Canyon. It is out of sight of Chaco Canyon. Even though Pueblo Pintado is also out of direct sight of Chaco Canyon, it is still part of the central design (sitting on a minor lunar standstill azimuth), in a way that Whitehorse is not. In or about Whitehorse, particularly along the fringes of Chacra Mesa, privacy can be found.

From "Breaking Bad, Season 5b, episode 6, 'Ozymandias':

W.: Listen, I was thinking, um, maybe we can have a little family time this weekend.

S.: Oh yeah?

W.: Yeah! You know, just take a drive; the almost four of us. (nervous laugh) Maybe we can head up the Turquoise Trail and stop at Tinkertown; maybe grab some lunch in Madrid.

S.: Omigod, we haven't been there in forever.

W.: I know, and so, why don't we just do that? Take a little break.

S.: Sold. Sounds fun!

So, Walt and Skyler decide to take their family on a metaphorical "Turquoise Trail". What could go wrong? Maybe history is a guide.

Turquoise is a blue mineral, akin to blue meth in terms of color:

Like the Aztecs, the Pueblo, Navajo and Apache tribes cherished turquoise for its amuletic use; the latter tribe believe the stone to afford the archer dead aim. Among these peoples turquoise was used in mosaic inlay, in sculptural works, and was fashioned into toroidal beads and freeform pendants. The Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) of the Chaco Canyon and surrounding region are believed to have prospered greatly from their production and trading of turquoise objects.

Anasazi commerce centered on one item: turquoise. Trading groups from the Toltec merchants' capital (Tollan or Tula) in central Mexico visited regularly. Chaco governors tightly controlled the turquoise mines at Cerrillos. Raw stone was brought to Pueblo Bonito to be cut into small tiles, which the merchant-traders took back to Tollan for use in jeweled and tiled creations. Trade must have diffused from the north, too, because in Chaco and other Anasazi sites are found many small beads and inlays made of carved caitlinite -- pipestone -- from Minnesota and Great Lakes quarries.... Foreign trade, through the rigidly-controlled Cerillos turquoise mines, was the major source of wealth -- foreign luxury products -- of the Anasazi civilization.

Turquoise was also a local medium of exchange -- a kind of money. About 5,000 people lived permanently in the towns of Chaco Canyon in 1100 AD (and tens of thousands visited for big fairs and ceremonies). But in spite of their ingenuity with waterworks, there was arable land near enough to work to feed only 2,000.

...[T]he 3-pronged disasters struck. First came Chaco's loss of control of turquoise sources. New mines opened up in Arizona and Nevada. ... Competitive turquoise trade with their best and only large customer -- the Toltec empire -- began with those uncontrolled mines, but considerable uncontrolled turquoise also entered the Chaco economy, devaluing it as turquoise became more common. More turquoise in circulation was a kind of inflation. Then the foreign market collapsed, as a civil war destroyed the Toltec empire (around 1100 AD). There was no longer a large foreign customer for the turquoise. No more foreign trade. Even more turquoise from the uncontrolled mines flooded the Anasazi economy, further inflation.

The final disaster was a 50-year drought, beginning in 1130. Ingenuity in channeling and storing water could not save the worsening situation. Food became very scarce. The outlying villagers had no surplus to bring to the markets in Chaco. ... So the Anasazi began to leave -- not only Chaco Canyon, but other large Anasazi centers established in cliff caves, like those at Mesa Verde.

...The Anasazi people did not mysteriously vanish. They moved in stages, taking with them most of their valuables, to establish the string of pueblos along the Rio Grande and a few other desert rivers. By 1200 AD, the Chaco Canyon center, and most high desert settlements of the Anasazi civilization were entirely deserted. The turquoise road over the Mexican High Sierra was forgotten, except probably for Mexico-based rumors people there later told the invading Spaniards: about 7 cities of gold somewhere to the north.

So, the trade in Anasazi blue turquoise is analogous to Walt's trade in blue meth.

What is the analogy between Anasazi society and modern society? One natural advantage of the Southwest is very clear air. Plus the locality of Chaco Canyon is fairly-compact, allowing most of 'downtown Chaco' to be seen by just a few people appointed to the task. Thus, the rulers of Chaco Canyon might have inclined to use sight to maintain control of their society. That feature has a distinct modern edge, however. Discipline in modern societies relies a lot on sight.

Last year at the SWPCA, Jeff Pettis drew attention to the uses of sight in "Breaking Bad": Walt, who continually seeks a Panoptic point; Lydia, who always seeks to evade detection, and Gus, who hides in plain sight. Who can see who, and how, is very important in "Breaking Bad".

As Jeff Pettis notes, Michel Foucault has written about the use of sight to discipline people:

Jeremy Bentham proposed the panopticon as a circular building with an observation tower in the centre of an open space surrounded by an outer wall. This wall would contain cells for occupants. This design would increase security by facilitating more effective surveillance. Residing within cells flooded with light, occupants would be readily distinguishable and visible to an official invisibly positioned in the central tower. Conversely, occupants would be invisible to each other, with concrete walls dividing their cells. Although usually associated with prisons, the panoptic style of architecture might be used in other institutions with surveillance needs, such as schools, factories, or hospitals.Chaco Canyon is a natural Panopticon. Views across most of the central area of power at Pueblo Bonito are easy to obtain. Just a few people could observe society from Pueblo Bonito, or from one of the Tower Kivas, and thereby economically control virtually the entire political life of the Canyon. Even though it was a premodern society, Chaco Canyon at least contained this element of modern society: power mediated by the direct view. Perhaps like the Panopticon, Chaco Canyon experienced other phenomena that might be considered modern too: e.g., an abrupt change of power, aka a revolution.

In "Discipline and Punish", Michel Foucault builds on Bentham's conceptualization of the panopticon as he elaborates upon the function of disciplinary mechanisms in such a prison and illustrated the function of discipline as an apparatus of power. The ever-visible inmate, Foucault suggests, is always "the object of information, never a subject in communication". He adds that:

"He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself; he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection."...As hinted at by the architecture, this panoptic design can be used for any "population" that needs to be kept under observation or control, such as: prisoners, schoolchildren, medical patients, or workers:

The drought of the mid-1100's was a major challenge:

According to the National Park Service World Heritage Program, drought was a factor in the abandonment on Chaco during the 12th Century:More climate data are available from the Grissino-Mayer dissertation from U of A in 1995 based on tree-ring data from the Malpais near Grants.

"The decline of Chaco apparently coincided with a prolonged drought in the San Juan Basin between 1130 and 1180. Lack of rainfall combined with an overtaxed environment may have led to food shortages. Even the clever irrigation methods of the Chacoans could not overcome prolonged drought. Under these pressures Chaco and the outliers may have experienced a slow social disintegration. The people began to drift away."During the 13th Century, the Ancient Pueblo peoples of Mesa Verde and nearby regions also abandoned their masonry homes. For many decades the conventional wisdom was that severe drought pushed them from the region due to crop failures. Paleo proxy data from tree rings and packrat middens have been used as evidence that a severe drought had hit the region. Analysis of bones from the inhabitants which showed malnutrition seemed to confirm the drought theory.

The drought of the 1100's eased in the 1190's. The early 1200's were a wet period - but a much-worse drought occurred in the 1240's.

Still, it is likely that as wealth departed Chaco Canyon and drought decimated the civilization, the power elite clung to power. Civilizations usually don't change leadership when conditions are deteriorating.

There are a number of theories regarding the nature of revolutionary change in societies - France, Russia, and Iran provide notable examples. In all three cases, serendipitous accidents combine with long-standing grievances to produce unexpected results:

The French Revolution, Tocqueville ... notes, drew much of its strength from districts near Paris where 'the freedom and wealth of the peasants had long been better assured than in any other [district].' Under the influence of the democratic ideas in the air, King Louis XVI and his men had simply 'lost the will to repress'. In Iran, the impetus for reducing repression seems to have come from U.S. President Jimmy Carter's human rights campaign. Aiming to preempt Carter to avoid the appearance of being pressured by the U.S., the Shah took some measures on his own initiative: he gave the press more freedom and permitted open trials for civilians brought before military tribunals .... Regardless of the merits of the measures themselves, it stands to reason that they helped the opposition grow. If hatred for the government is widespread, providing greater opportunities for criticism serves to publicize this fact, thereby encouraging more people to side openly with the opposition. Also significant no doubt is the Shah's vacillation with regard to the use of force against the growing crowds, perhaps because the cancer treatment he was receiving impaired his judgment. Inasmuch as vacillation is seen as a sign of weakness, it raises the relative attractiveness of joining the opposition.So, improving conditions are often crucial to revolutions, because discontented folks can easily imagine improved circumstances if only the leadership is changed. Various incidents and accidents are important too, as they provide occasions when power can be directly challenged.

... The following remarks by Tocqueville are telling:

[I]t is not always when things are going from bad to worse that revolutions break out. On the contrary, it oftener happens that when a people which has put up with an oppressive rule over a long period without protest suddenly finds the government relaxing its pressure, it takes up arms against it. Thus the social order overthrown by a revolution is almost always better than the one immediately preceding it, and experience teaches us that, generally speaking, the most perilous moment for a bad government is one when it seeks to mend its ways....The Russian Revolution, it appears, was ignited by a major strategic error on the part of the authorities, coupled with a series of coincidences. The Petrograd regiments normally responsible for protecting the Tzar were at the front in early 1917, and most of their replacements were new recruits who were not only less well trained and less experienced, but also more attuned to the mood of the civil population. This proved to be a grave error, since the new regiments fell apart as they came in contact with the crowds.... It is well worth reiterating in this connection that no one, not even Lenin and his fellow revolutionaries, foresaw that the regiments in Petrograd would melt away when called on to control the crowds.

But what brought the crowds into the street in the first place? Four factors seem to have played a role. On 23 February, the day the uprising began, many residents of Petrograd were standing in food queues, because of rumors that food was in short supply. 20,000 workers were in the streets after being locked out of a large industrial complex. Hundreds of off-duty soldiers were outdoors, looking for a distraction. And as the day went on, multitudes of women workers left their factories early to march in celebration of Women's Day.... The combined crowd quickly turned into a self-reinforcing mob. It managed to topple the Romanov dynasty within four days.

But the Anasazi based their spiritual power on astronomical understanding. The only really reliable way to carry out a revolution against their power elite was for some unexpected astronomical event to undermine the leadership. What kind of event would that be?

One possibility would be the Crab Nebula Supernova of 1054 A.D. It was completely unexpected. Still, the realm of the stars was not the primary competency of Anasazi leadership: the cycles of the Sun and the Moon were. The Crab Nebula Supernova of 1054 A.D. likely wasn't the triggering event.

Total solar eclipses are very rare at Chaco Canyon, occurring typically once a century. There was one particularly dramatic total solar eclipse in the 1100's, however, on April 22, 1194: a "Black Dawn" - total solar eclipse at sunrise. In addition, there was a second partial solar eclipse on September 23, 1196, which wasn't a total eclipse, but did occur at a sensitive time: Autumnal equinox in a minor lunar standstill year.

Perhaps it is easier to answer a narrower question. Making the following assumptions about the Anasazi:

- they did not have an overarching theory of how solar eclipses occurred;

- they experienced eclipses as a time series of events;

- they carefully recorded when eclipses occurred;

- they tried to predict future eclipses based on past behavior;

Solar eclipses follow complicated patterns known as saros (close to 18 years in length - about 11 days longer), and inex (about 29 years - minus 20 days) cycles.

At Chaco Canyon over a 250 year period (850-1200: representing the zenith of Anasazi power), roughly 30 of the 40-or-so operating saros cycles at the time would have been observed. Saros cycles repeat at 18 year intervals, but eclipse locations move about the Earth, so at any one point on the Earth (like Chaco Canyon) saros cycles may skip, and detecting the underlying 18-year saros pattern is difficult. Similarly, inex cycles skip too. It is easier to observe the 54-year triple-saros 'exeligmos' cycle (54 = 3 * 18), since the eclipse location will be nearly the same as 54 years before.

A Fourier Transform of the eclipse frequency over 260 years fails to show either the saros, triple saros, or inex cycles. Instead, different, ephemeral cycles appear: 12, 39, 50, 72, and 104 year cycles. The 72-year cycle is four saros cycles (4 * 18 = 72) and so the underlying 18-year pattern is present. Still, the underlying 18-year pattern can't be resolved easily by a Fourier transform.

A Fourier Transform of the eclipse frequency over 260 years fails to show either the saros, triple saros, or inex cycles. Instead, different, ephemeral cycles appear: 12, 39, 50, 72, and 104 year cycles. The 72-year cycle is four saros cycles (4 * 18 = 72) and so the underlying 18-year pattern is present. Still, the underlying 18-year pattern can't be resolved easily by a Fourier transform.By the 1190's, the drought was easing. Conditions were improving. Dramatic signs of incompetence in the leadership predicting eclipses might be enough for a restless population to rebel. Chaco Canyon's Panopticon could easily turn into Synopticon as the leadership lost face due to a dramatic, unanticipated eclipse. Presumably under new leadership, Chaco Canyon’s great kivas were decommissioned and filled with dirt. The population left, and escorted the old leadership out of Chaco Canyon.

There are indications the population split in two, with some people migrating north to Aztec and others farther north to Mesa Verde. Archaeologist Steve Lekson has proposed that, after a residency at Aztec, the old leadership might have eventually migrated south, to Casas Grandes in northern Mexico (Fagan, 2005).

Interestingly, there is another inference about Native American society that can be inferred from these speculations. I wondered whether the Red Mountain located near Chaco Canyon is the same Red Mountain that is one of the sacred Navajo Mountains. According to "Sacred Places of the Navajo", it isn't. But there is a curious fuzziness about the location identified as Red Mountain. It is said to be five miles northeast of San Luis, NM, but there is no mountain there. There is Cerro Colorado, a range of hills, five miles north of San Luis, NM, but the story told by the Navajo about the location doesn't jive very well with Cerro Colorado. The story features hot springs and a cave:

This sacred prominence, about five miles northeast of San Luis, N.M., was said by Frank Goldtooth to have been the ninth mountain created in this world, by Begochidi, preceded by Ragged Mountain and succeeded by Reversible Mountain (q.v. ). It is at the center of the world (but see Gobernador Knob). Begochidi next created the ants, and sent them to the mountains he had made; from these derived all the other, flying, insects. First Man planted Big Bamboo in the center of Red Mountain. He and First Woman also planted various reeds and other plants.

In several versions of the Navajo Windway, the myth's basic motif, the snake transformation, takes place at "Hot Spring" on Red Mountain. The hero is turned into a snake by Big Snake for having shot and/or eaten here a deer or other animal that was Big Snake in disguise, or belonged to him. Talking God came to inform the man's family that the man was now a snake. Big Fly recommended that Wind People be summoned from "Coiled Mountain," near Mt. Taylor, where the man also lived. Offerings made to the snakes at Dark Wind's suggestion were rejected, so Dark Wind set up four hoops near Big Snake's cave. After Thunder knocked the snake out, it was thrown through each hoop, and in the process sloughed off its skin and became a man once more. A (Striped) Windway was performed to restore his voice and his health, and this is the origin of that ceremonial. Against Big Wind's advice, the man married Big Snake's daughter, who bore many, many snakes. He realized his error, and later moved to another mountain and became a Wind God, who manifests himself in tornadoes.

Cerro Colorado is pretty dry: no apparent hot spring; no known cave. But there is a place not far away where these features can be found. San Ysidro Hot Springs might be the hot spring; Alabaster Cave (Ojo del Diablo) might be the cave, and Red Mesa, immediately adjacent to the Jemez Valley, might be Red Mountain. Or at least it seems so to me. Maybe that explains the ferocity of the old fights between the Navajo and the Jemez. But then, I should be more humble. There may be Navajo elders who know the answer. And at the end of the day, maybe it's their business.

References:

Jeff Pettis

"Sacred Places of the Navajo", by Stephen C. Jett and Editha L. Watson

"Foucault - A Very Short Introduction", Gary Gutting, Oxford University Press, 2005.

"Foucault For Beginners", Lydia Alix Fillingham, Writers and Readers Publishing, 1993.

"Chaco Astronomy - An Ancient American Cosmology", Anna Sofaer and Contributors to The Solstice Project, Ocean Tree Books, 2008.

"Chaco Canyon - Archaeologists Explore The Lives Of An Ancient Society", Brian Fagan, Oxford University Press, 2005.

No comments:

Post a Comment