Links to 28 different "Breaking Bad" and "Better Call Saul" posts can be found on the sidebar of the Marc Valdez Weblog desktop website. Choose the link that works best for you.

This post focuses on the history of To'hajiilee and its influence on "Breaking Bad" (updated on March 28, 2025).

Let me know if you have any problems or questions (E-Mail address: valdezmarc56@gmail.com).

Let me know if you have any problems or questions (E-Mail address: valdezmarc56@gmail.com).

--------------------------

"A Guidebook To 'Breaking Bad' Filming Locations: Including 'Better Call Saul' - Albuquerque as Physical Setting and Indispensable Character" (Sixth Edition)

Purchase book at the link. This book outlines thirty-three circuits that the avid fan can travel in order to visit up to 679 different filming locations for "Breaking Bad" and "Better Call Saul" in the Albuquerque area. Some background is provided for each site, including other movies that might have also used the site for filming.

"‘Breaking Bad’ Signs and Symbols: Reading Meaning into Sets, Props, and Filming Locations” (Second Edition)

Purchase book at the link. “‘Breaking Bad’ Signs and Symbols,” aims to understand some of the symbolism embedded in the backgrounds of “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul,” in order to decode messages and stories Vince Gilligan and crew have hidden there. A series of tables are used to isolate how certain (particularly architectural) features are used: Gentle Arches, Tin Ceilings, Five-Pointed Stars, Octagons, etc. Daylighting innovations that were either pioneered or promoted in Chicago are examined: Glass Block Windows, Luxfer Prismatic Tile Windows, and Plate Glass Windows.

Certain symbols advance the plot: foreshadowing symbols like Pueblo Deco Arches, or danger symbols like bell shapes and stagger symbols. Other features, like Glass Block Windows or Parallel Beams in the Ceiling, tell stories about the legacies and corruptions of modernity, particularly those best-displayed at Chicago’s “Century of Progress” (1933-34).

To avoid unnecessary friction, I have redacted the addresses of all single-family homes in these books. (These addresses are still available at Marc Valdez Weblog, however.) The pictures in the print editions are black-and-white, in order to keep costs down.

"A Guidebook To 'Breaking Bad' Filming Locations: Including 'Better Call Saul' - Albuquerque as Physical Setting and Indispensable Character" (Sixth Edition)

Purchase book at the link. This book outlines thirty-three circuits that the avid fan can travel in order to visit up to 679 different filming locations for "Breaking Bad" and "Better Call Saul" in the Albuquerque area. Some background is provided for each site, including other movies that might have also used the site for filming.

"‘Breaking Bad’ Signs and Symbols: Reading Meaning into Sets, Props, and Filming Locations” (Second Edition)

Purchase book at the link. “‘Breaking Bad’ Signs and Symbols,” aims to understand some of the symbolism embedded in the backgrounds of “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul,” in order to decode messages and stories Vince Gilligan and crew have hidden there. A series of tables are used to isolate how certain (particularly architectural) features are used: Gentle Arches, Tin Ceilings, Five-Pointed Stars, Octagons, etc. Daylighting innovations that were either pioneered or promoted in Chicago are examined: Glass Block Windows, Luxfer Prismatic Tile Windows, and Plate Glass Windows.

Certain symbols advance the plot: foreshadowing symbols like Pueblo Deco Arches, or danger symbols like bell shapes and stagger symbols. Other features, like Glass Block Windows or Parallel Beams in the Ceiling, tell stories about the legacies and corruptions of modernity, particularly those best-displayed at Chicago’s “Century of Progress” (1933-34).

In addition, a number of scenes in the show are modeled after Early Surrealist artworks. The traces of various artists can be tracked in both shows, including: Comte de Lautréamont, Giorgio De Chirico, Man Ray, Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington, René Magritte, Toyen, Yves Tanguy, Remedios Varo, Paul Klee, and in particular, Salvador Dalí.

--------------------------

I was pleased to see the eye-catching opening scenes of the TV series take place in To'hajiilee (formerly Cañoncito), the outlier Navajo reservation northwest of Albuquerque.

I was pleased to see the eye-catching opening scenes of the TV series take place in To'hajiilee (formerly Cañoncito), the outlier Navajo reservation northwest of Albuquerque.I always felt a little bit puzzled by the choice of To'hajiilee as a filming location. There are a number of sound practical and cinematic reasons to film in To'hajiilee, but there is also a deeper history to the area. I wondered if the writers of TV show were trying to make a deeper statement about "Breaking Bad", perhaps by using the history of To'hajiilee as a form of foreshadowing about the show's conclusion at the end of Season 5. The tragic history of To’hajiilee establishes a "Miasma" (a classical Greek term ) – the brooding atmosphere that prefigures the opening of the story.

In a way, despite its modernity, "Breaking Bad" is a parable about the Old West. Like William Faulkner said: "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

First, the practical reasons why To'hajiilee makes sense as a filming location.

First, the practical reasons why To'hajiilee makes sense as a filming location. The closest approach of the Colorado Plateau to the city of Albuquerque, where "Breaking Bad" is filmed, is the area around To'hajiilee, and so if you want to incorporate that classic, panoramic red-sandstone-mesa look of the Southwest's Colorado Plateau into your TV show, and still minimize travel distance and thus remain on-budget, To'hajiilee is an obvious place you would want to film.

Still, there is that deeper layer of history....

Pekka Hämäläinen's book, "The Comanche Empire" (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2008), opens a new way to understand Spanish approaches to and attitudes towards Native Americans. The Spanish were in a position of considerable weakness in regards to the tribes of North America, and did their utmost to leverage their access to European technology to manipulate and control the menacing neighboring tribes, in particular, the Comanche, and then the Navajo.

Here are some extended quotes from Hämäläinen's book:

[p. 107] On February 25, 1786, Juan Bautista de Anza, lieutenant colonel in the Spanish Army and the governor of New Mexico, stood in front of his palace, preparing himself for the ceremony. He had waited for this moment too long, ever since the glorious day on the llanos seven years ago when he held the green-horned headdress in his hands [headdress trophy from his defeat of Comanche chief Cuerno Verde in 1779]. The memory of his triumph was already growing faint, making his gubernatorial tenure seem like a failure, but now there was hope again. He examined his subjects - hispanos, indios, genízaros, men, women, children - who swarmed in the dirt plaza, filling it with nervous expectation. Then the crowd shivered, erupting into shrieks and yells, and Anza saw him. Ecueracapa, the capitan general of the western Comanches, emerged at the end of a corridor of shouting people. The Indian rode slowly toward him, flanked by three adjutants and escorted by a column of Spanish soldiers and Santa Fe's most prominent citizens. He calmly crossed the square, dismounted in front of Anza, and gently embraced him. It was there, in the arms of the man he could think of only as a savage, that Anza knew there would be peace.The Comanches were desirous of peace because they faced renewed hostilities with other tribes, and they had been suddenly weakened by epidemics. Ecueracapa made the peace overtures, starting in December 1785. Having captured Chiquíto, an Indian member of a plains-bound Spanish hunting party who also spoke Comanche, Ecueracapa:

[pp. 118-119] called together four consecutive councils to discuss details of peace talks and, having reached an agreement with the other chiefs, sent Chiquíto and two Comanche envoys to inform Anza that he would be arriving shortly in Santa Fe.Anza took quick advantage of the new arrangement:

The announcement electrified the Southwest, where news traveled quickly....

Word of the forthcoming Comanche-Spanish negotiations also reached the Utes, who were outraged by the new Spanish policy. Having nurtured a stable and mutually beneficial alliance with New Mexico since mid-century - an alliance that had been sustained by common dread of the Comanches - they now feared that Comanche-Spanish rapprochement would leave them marginalized and exposed to Comanche violence. They met with Anza and "heatedly declared against the attempted peace, advancing the most vindictive and even insulting and barbarous arguments against it, even stating to the chief, Anza, that he preferred frequent, unfaithful rebels to friends always obedient and faithful."

[pp. 123-124] The Comanche treaty was a momentous coup for Anza and it gave him leverage to enter into negotiations with the powerful Navajos who dominated a vast territory west of New Mexico. In March 1786, only weeks after the conclusion of the Comanche talks, Anza invited Navajo leaders to a peace conference. His objective was to pacify the Navajos by forcing them to resign their alliance with the Gileño Apaches, and he had laid the ground for this move a year before when he banned all trade between the Navajos and the inhabitants of New Mexico. Now eighty Navajos came to meet him in Santa Fe, where, significantly, a small Comanche delegation was also present. When the talks between Anza and Navajo leaders began in the Governor's Palace, two Comanches, at Anza's request, made a surprise entrance "so that the Navajos, having seen them, might be moved by fear and respect they have for this warlike nation." According to Garrido's report, one of the Comanches demanded that the Navajos become Spain's allies, lest "the forces of the Comanches as good allies and friends of the Spaniards would come and exterminate them. He menaced and terrorized them so much that with the same submission which the governor [received] they replied to the Comanches that they would fail in nothing agreed upon." The Navajos agreed to a treaty in which they pledged to sever ties with the Gileños, form a military alliance with Spain, and enter a nonaggression pact with the Comanches. The resulting borderlands détente, midwifed by Comanches, served Comanche interests as much as it served Spanish ones: if Comanches were to develop closer commercial interests with New Mexico, they needed the colony to be safe and prosperous.The Spanish appointed Don Carlos of the Cebolleta branch of the Navajo as "chief of the Navajos" was in 1786 - likely at this very meeting. Despite his rank, the other Navajo leaders did not submit to Don Carlos as their leader. The Navajos were more-atomized and politically not as well-organized as the Comanches. Ecueracapa, through incessant travel and diplomatic activities all across Comanchería, had achieved a first-among-equals sort of rank among Comanches, and could speak broadly for most of them, but Don Carlos wasn’t in such a position.

Still, the 1786 meeting was the start of a process whereby the Diné ‘Ana’í slowly came to identify their interests more-closely with the Spanish than with their fellow Navajo, which culminated with Joaquín's separation of the Cebolleta band from the rest of the Navajo in order to negotiate a separate peace, in about 1818. One can imagine that hastening trade with the Americans, eastward, across what would become the Santa Fe Trail, made good relations with the Spaniards more important than ever to sustain. And the vulnerable Cebolleta band was located on the eastern flanks of what was to become Mt. Taylor, squarely between the Spanish and the rest of the Navajo.

And so, what was the Spanish method to induce compliance? Hämäläinen continues:

[p. 132] Rather than trying to incorporate or contain indigenous societies, the new objective was to transform them into an entity that Spanish agents could understand, manage, and control. ... Bourbon officials had initially thought that more authoritative Comanche leaders were needed to unite unruly Indians behind peace treaties, but once the treaties were formalized, the officials reconceived political centralization as a means to subdue their new allies. Inspired by pragmatic visions of a consolidated New Spain, the Bourbon officials had concluded that they never could bring the empire to Comanchería. Instead, they resolved to bring the Comanches into the empire.In the end, the Spanish were mostly-happy with their compact with the Comanche, and how well they controlled the Comanche. On the part, the Comanche were also happy with the compact, and with how well they controlled the Spanish. Nevertheless, the Spanish policy was never successful in reducing the Comanches to actual dependency. The Spanish simply needed the Comanche more than the Comanche needed the Spanish.

Bourbon officials applied the centralizing pressure most systematically on the western Comanches, whose continued loyalty they considered critical for the survival of New Mexico and, by extension, the silver provinces of northern New Spain. The policy was first articulated by Anza in 1786 when he argued that by elevating Ecueracapa "above the rest of his class" Spaniards could reduce the entire Comanche nation to vassalage. The idea was to create a well-defined hierarchical structure extending from the principal chiefs to the bottom of Comanche society through strategic distribution of political gifts. Accordingly, Spanish officials in New Mexico and Texas funneled vast amounts of gifts among the Comanches through Ecueracapa and other head chiefs, hoping to originate a downward flow of presents from Spanish authorities to principal chiefs, local band leaders, and commoners and, conversely, an upward-converging dependency network on top of which stood the king of Spain. The institution of principal chieftainship, as Pedro Garrido explained was "the most appropriate instrument that we could desire for the new arrangement of peace, not only to assure the continuance of the peace of the peace celebrated, but also to subject the warlike Comanche nation to the dominion of the king."

Most of the Navajos were also resistant to dependency. It was only the portions of the Navajo nation that were physically closest to the Spaniards that eventually did succumb.

There is an excellent book regarding the Navajo (also known as the Diné), portions of which are available online by Google Books for purchase: Spider Woman Walks This Land: Traditional Cultural Properties and the Navajo, by Kelli Carmean.

I quote below from specific specific passages, starting with a general overview of the Navajo, starting in the late 1700's:

Even though the Spanish largely ignored the Navajo, it does not mean the Navajo were spared from conflict. Throughout this time the Navajo were victims of slave raids from Utes, Comanches, Kiowas and Spaniards acting outside of official Spanish law. Although Spain had forbidden the enslavement of Indians, Spanish colonists felt free to ignore a mandate handed down from far across the Atlantic. Political leaders in the colonies supported the slave trade and the majority even actively participated. Sometimes the leaders kept the Indian captives in their own households, other times they gave the slaves away to gain political favors or to strengthen friendships. Although slave raiding was endemic to much of pre-contact Indian society, it increased greatly with the arrival of the Spanish, as they were ever-willing buyers and required vast numbers of slaves to work the silver mines of Mexico (McNitt 1972). To complicate the picture even more, periods of friendly trade relations beneficial to all existed as intervals of peace alternated with raiding. Thus, life in the southwest was hardly peaceful or predictable from anyone’s perspective.

...

Before European contact and indeed well into the 1800s, there was no political entity that could be described as the Navajo “tribe.” The highest degree of political unity that occurred was a periodic, regional assembly of local leaders, called the Naachid (Wilkins 1999). This gathering was a combination of ceremony – dancing and prayers for good crops – and political discussions, attesting to the interwoven nature of religion and politics. Women could speak freely at these gatherings and Naachid decisions were not binding on anyone present. The last Naachid was reportedly held in the 1850s or 1860s, before Navajo removal to Bosque Redondo. The overall lack of political unity can best be seen in raiding patterns: Navajos were just as likely to raid other Navajos as they were to raid Pueblos or other Indians (who were equally likely to raid the Navajo). Although all Navajo people shared a common language and culture, they were not politically unified and thus did not act as one group until the reservation era.

Coming from a stratified society where leadership was based either on heredity or formal appointment, the Spanish, Mexicans, and later the Americans were unwilling to accept the uncertainties of the egalitarian Navajo political system. The colonists wanted Indian leaders who could speak for the entire tribe, make treaties, enforce decisions, and punish those individuals who did not abide by the treaties. In an optimistic but futile effort to change the Navajo political system, first the Spanish and later the Americans simply appointed political leaders for the Navajo. Not surprisingly, the colonists appointed those individual Navajo headmen who were amenable to Spanish demands.

In 1786, the Spanish appointed Don Carlos, the first in a long line of appointed Navajo “chiefs” (Acrey 2000). Don Carlos was a headman from the Cebolleta area of New Mexico – which was much closer to the major Spanish settlements of Albuquerque and Santa Fe than were the majority of Navajo – who by this time had moved west into northeastern Arizona, in part to escape repeated slave raids. Due to the proximity of the Cebolleta band to the Spanish settlements, Don Carlos, as well as subsequently appointed “chiefs,” firmly believed that the Spanish were too strong a force to fight and that the only hope the Navajo had for survival was to forge a peace with them. Living closer to the Spaniards, it is likely that this group bore the brunt of Spanish retaliatory raids. Not surprisingly, the appointment of Don Carlos as “chief” was not recognized by the main body of Navajo.

By 1818, while the Mexicans struggled to gain their independence from Spain, the Navajo’s internal schism was solidified when Joaquin, also of the Cebolleta band, was appointed “chief.” From this point on, Joaquin separated his band from the rest of the Navajo in order to independently negotiate a peace. His band even fought alongside the Spanish, and later the Mexicans, against other Navajos. Bitter over this betrayal, the Navajo gave Joaquin and his band the name Diné ‘Ana’í (Enemy Navajo). The motives of the Diné ‘Ana’í are often debated (McNitt 1972; Trafzer 1982). Some scholars argue that the Enemy Navajo sued for peace because they considered fighting the Spanish fruitless; others contend that Joaquin and his followers aligned themselves with the Spanish for self-gain, profiting from increased access to livestock and slaves. Under several different leaders, the Diné ‘Ana’í served as scouts and soldiers for the Spanish, and after 1821, for the Mexicans. They would also fight with the next group to seek control of the Southwest, the Americans, thus contributing to the final military defeat of the Navajo.

The Diné ‘Ana’í were hardly the only people in history to discover that they had certain interests more in common with their neighbors than with their more-remote relatives, and they suffered much abuse for acting upon this discovery. Perhaps to the rest of the Navajo, the Diné ‘Ana’í had 'broken bad,' but the reasons were understandable.

The Diné ‘Ana’í were hardly the only people in history to discover that they had certain interests more in common with their neighbors than with their more-remote relatives, and they suffered much abuse for acting upon this discovery. Perhaps to the rest of the Navajo, the Diné ‘Ana’í had 'broken bad,' but the reasons were understandable.Nevertheless, some people tried harder than others to exploit the possibilities provided by the new system of power: particularly a fellow named Sandoval, who strikes me as a sort of Heisenberg of the Southwest, who used his leadership position to push harder than ever for advantages for his band, just as Walter White uses his chemistry skills and his control over Jesse in "Breaking Bad" to gain more and more command over the underground drug realm.

One of the most important events in the troubled history of Navajo/American relations had a Diné ‘Ana’í angle. There is another excellent book regarding the Navajo, portions of which are available online by Google Books for purchase: Canyon de Chelly, Its People and Rock Art, by Campbell Grant. The Google Reader is here: I quote below from specific passages regarding the Calhoun/Washington expedition of 1849 to the Navajo chief Narbona:

The expedition left Santa Fe August 16, and during the wait at Jemez for the rest of the party, Simpson and Edward Kern saw the Pueblo Green Corn Dance. Several days later Washington’s force of roughly 500 men began their movement west toward the Chuska Mountains. The chief guide for the movement into the Navajo heartland was Antonio Sandoval, chief leader of the Diné ‘Ana’í, or enemy Navajo. Their route took them through Chaco Canyon, a difficult route for the artillery and dragoons. The ruins in the canyon fascinated Simpson, who described them in great detail in his report. He also noted hieroglyphics (petroglyphs) on large sandstone boulders.

On August 30, contact was made with numbers of the Navajo in the Tunicha Valley, and the following day Washington began talks with some of the headmen. Among them was the venerable Narbona, a much respected leader, whom the Anglos mistook for the “head chief of the Navajo,” and two other prominent men, Jose Largo and Archuleta, both of whom had been signers of the Doniphan treaty. Colonel Washington and Agent Calhoun asked the chiefs to assemble the leading men of the tribe at the mouth of Canyon de Chelly, where a lasting treaty of peace could be signed. All were agreeable to this, and the meeting was about to break up when an incredible incident occurred.

A Pueblo Indian irregular claimed to have spotted one of his horses in the Navajo party. On hearing this, Colonel Washington demanded that the animal immediately be returned or he would order his troops to fire on the Navajo. After receiving this hostile ultimatum, the Diné began to ride off, receiving rifle and cannon fire as they fled. The result of this unbelievably stupid move on Washington’s part was that six Navajo warriors were mortally wounded and the headman Narbona was killed. From that moment, the Navajo put no further trust in the Anglo-Americans, considering them as treacherous as their ancient enemies, the Mexicans.

I just think Sandoval was pushing his luck by getting mixed up with this expedition. In part through his efforts, Sandoval got Narbona killed, a case of overreach that may be analogous to how Walt gets Gus killed in "Breaking Bad". (It's interesting about the coincidence of names too: the Navajo headman Archuleta, and the janitor in Walt's school, Mr. Archuleta, whose job and freedom Walt sacrifices without a moment's hesitation).

In any event, this political system based on infighting eventually shattered when the Navajo were brought under the ethnic-cleansing sway of fanatical General Carleton by his able assistant, the former Mountain Man, Kit Carson. All Diné were crushed, whatever their association with the Americans.

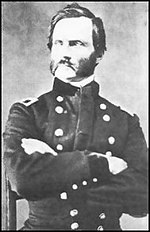

Above: Brig. Gen. James Henry Carleton, who presided for a time as New Mexico's virtual dictator, and whose Utopian visions for the Navajo ended up decimating the tribe.

In his book about Kit Carson, "Blood and Thunder: The epic story of Kit Carson and the conquest of the American West", Hampton Sides writes about Brig. Gen. James Henry Carleton:

For the next four years he would preside over New Mexico virtually as a dictator. But he was an uncommon kind of despot: a Puritan schoolmaster with a zeal for social engineering, a martinet of the cod liver-oil dispensing, this-is-for-your-own-good variety. He was a utopian in an odd sense, and a Christian idealist. Carleton saw a perfect world on the horizon but could not imagine the real-world horrors that would be required to reach it."

Quoting from Wikipedia:

On October 31, 1862, Congress authorized the creation of Fort Sumner. General James Henry Carleton initially justified the fort as offering protection to settlers in the Pecos River valley from the Mescalero Apaches, Kiowa, and Comanche. He also created the Bosque Redondo reservation, a 40-square-mile (100 km2) area where over 9,000 Navajo and Mescalero Apaches were forced to live because of accusations raiding white settlements near their respective homelands. The fort was named for General Edmond Vose Sumner.And as Carmean also writes:

The stated purpose of the reservation was for it to be self-sufficient, while teaching Mescalero Apaches and Navajos how to be modern farmers. General Edward Canby, whom Carleton replaced, first suggested that the Navajo people be moved to a series of reservations and be taught new skills. Some in Washington, D.C. thought that the Navajos did not need to be moved and a reservation should be created on their land. Some New Mexico citizens encouraged death or at least complete removal of the Navajo off their lands. The 1865 and 1866 corn production was sufficient, but in 1867 it was a total failure. Army officers and Indian Agents realized that the Bosque Redondo was a failure, offering poor water and too little firewood for the numbers of people who were there. The Mescaleros soon ran away; the Navajos stayed longer, but in May 1868 were permitted to return to Navajo lands.

Gen. Carleton ordered Col. Christopher "Kit" Carson to do whatever necessary to bring first the Mescaleros and then the Navajos to the Bosque Redondo. All of the Mescalero Apache were there by the end of 1862, but the Navajo did not get there in large numbers until early 1864. The Navajos refer to the journey from Navajo land to the Bosque Redondo as the Long Walk. While a bitter memory to many Navajo, one who was there reports as follows: “By slow stages we traveled eastward by present Gallup and Shushbito, Bear spring, which is now called Fort Wingate. You ask how they treated us? If there was room the soldiers put the women and children on the wagons. Some even let them ride behind them on their horses. I have never been able to understand a people who killed you one day and on the next played with your children...?"

There were about 8,500 Navajo and 500 Mescalero Apaches interned at Bosque Redondo in April 1865. The Army had only anticipated 5,000 would be there, so food was an issue from the start. The Navajo and Mescalero Apache had long been enemies and now that they were in forced proximity to each other, fighting often broke out. The environmental situation got worse. The interned people had no clean water, it was full of alkaline and there was no firewood to cook with. The water from the nearby Pecos River caused severe intestinal problems and disease quickly spread throughout the camp. Food was also in short supply because of crop failures, Army and Indian Agent bungling, and criminal activities. In 1865, the Mescalero Apaches, or those strong enough to travel, managed to escape. The Navajo were not allowed to leave until May, 1868 when it was agreed by the U.S. Army that Fort Sumner and the Bosque Redondo reservation was a failure.

A treaty was negotiated with the Navajos and they were allowed to return to their homeland, to a "new reservation." There they were joined by the thousands of Navajo who had been hiding out in the Arizona hinterlands. This experience resulted in a more determined Navajo, and never again were they surprise raiders of the Rio Grande valley. In subsequent years they have expanded the "new reservation" into well over 16 million acres (65,000 km²), far larger than Yellowstone National Park with 2 million acres (8,000 km²).

Between 1864 and 1868, just over 8,000 Navajos were taken to Bosque Redondo. This number was much greater than the military had expected; their resources were overwhelmed and their facilities incapable of dealing with so many people, especially a people already worn down both physically and psychologically from Kit Carson’s campaigns and the Long Walk. Although Carleton’s plan was to have the Navajo build irrigation canals and grow their own food, this plan was never successful and the crop failed each year. Completely dependent on the government for food, Navajo rations were tight. Local Anglo merchants, knowing they had a monopoly for government supplies in isolated eastern New Mexico, price-gouged the Army, providing a minimum quantity of food for maximum prices. Navajo oral histories tell of eating flour crawling with bugs and boiling shoe leather for meat because they had no choice.And so, how were the terrible tensions among the Navajo resolved? By physical separation:

...

As can be imagined, many problems existed at Bosque Redondo. The Navajo joined an estimated four hundred Mescalero Apaches, traditional enemies of the Navajo, also confined to the reservation. The Diné ‘Ana’í were also there; indeed, since they put up no resistance, they were the first to go to the Bosque. Thus, it was difficult to sort out who were the worst enemies – likewise incarcerated Indians or the U.S. Army. Slave raiding against the Navajo continued and any Navajo that wandered just a little too far in search of firewood was picked up by Kiowas and Comanches lying in wait. The Navajo, of course, were weaponless.

After the June 1 signing of the treaty of 1868, the Navajo prepared to return to their homeland. They returned to Navajoland just as they had departed – walking. On June 18, the first and largest return group moved slowly out of Fort Sumner, a column stretching ten miles long.And today, Cañoncito is known as To'hajiilee.

As the column neared Fort Wingate, near present-day Gallup, New Mexico, three small but important groups split off from the main return party. Two of these groups were composed of the Diné ‘Ana’í. Even during the four-year stay at Fort Sumner, these internal divisions did not heal, and these Navajo split off from the main body and went to live on their own, eventually becoming known as the Cañoncito Band. Another group of Diné ‘Ana’í spilt off and headed south, eventually becoming known as the Alamo Band. The Ramah Band also emerged at this time, as other returning Navajo went to join relatives who had escaped from Bosque Redondo some time earlier. Today, the Navajo reservation still includes these three Navajo enclaves removed from the main reservation. Although the Treaty of 1868 did not allow for such splintering and occupation of nonreservation lands, nothing was done to stop it. It was not until the 1940s and early 1950s that the land occupied by these three geographically isolated groups was converted into reservation land.

Presumably, after 140 years, these tensions among the Navajo have been resolved. Cultural unity is ultimately much-more important than any political division exploited for temporary gain.

Presumably, after 140 years, these tensions among the Navajo have been resolved. Cultural unity is ultimately much-more important than any political division exploited for temporary gain.Still, it's interesting history. Fanatical visions imposed from above eventually destroyed the temporary advantages of treachery from within. "The past is never dead. It's not even past." And one must remember, To'hajiilee is literally the very ground from which "Breaking Bad" starts.

As Season 5 of "Breaking Bad" starts (the final season), what treachery from within might we expect between Walt and Jesse, and what might eventually shatter the temporary peace reached at the end of Season 4? Will there be a physical separation? Will Skyler take the baby and flee to Colorado, as foretold by her flipping coin (Season 4, episode 6, 'Cornered')? Is there a fanatical drug lord out there who will arrive to impose his will on Walt and Jesse; perhaps even one of the "cod liver-oil dispensing, this-is-for-your-own-good variety"? Or is Hank, Walt's dogged brother-in-law, the true fanatic, the man who will destroy all in his efforts to set all things right?

Im so very glad that they did some of the filming in Tohajiilee. YES.

ReplyDeleteAbout time they did somethng with that place. It just seems that we Navajos in Tohajiilee are forgotten. I am from there. We would love to see more of it in the near future. Again thanks, THE YAZZIE FAMILY.

Thanks for the good wishes!

ReplyDeleteWho knew that when they first filmed there, in 2007, that critics would come to view "Breaking Bad" as the best TV series ever aired? It is a real blessing that Tohajiilee is now linked so closely to the show. I'm thinking that, especially in Season 5, that there are odd parallels between Navajo stories and the progress of the show - as if the show's script was Navajo legend, as interpreted by mafiosi. I'd like to know more about the history of Tohajiilee, in part, to understand if these parallels are accidental, or carefully planned.