I wonder how the Chaco Canyon Sun Dagger is doing these days?

I visited this interesting archaeoastronomical site in 1980, just before Chaco Canyon National Monument Park officials closed it to public visits (following Anna Sofaer's realization of the site's importance in 1977, the Sun Dagger was becoming increasingly popular, and the officials worried they couldn't control the escalating number of visitors). The Anasazi (ancestors to the Pueblo Indians) had considerable interest in astronomy, evidenced, among other things, by their record of the Crab Nebula Supernova in A.D. 1054.

Part of of this interest might be part of a larger, general interest in ancient America in astronomy. Even though there was certainly a large cultural difference between the Anasazi, and the civilizations of Mexico far, far to the south (evidence: ball courts, ubiquitous in Mexican Indian pueblos, are found no farther north than the Hohokam pueblos of southern Arizona), there certainly were trade networks throughout the Americas: Cerrillos, NM turquoise has been found in central Mexico, and sea shells and macaw bones have been found in Chaco Canyon. Macaw bones! Amazing! Macaws live in Panama! People had to carry the large birds, presumably in cages (but if their wings were clipped, maybe not) thousands of miles over the most rugged country on their backs (since the Indians didn't have pack animals larger than dogs).

Anyway, in the summer of 1980, Ira G., Steve M. and his brother, the brothers Otii, and myself clambered up Fajada Butte, using ropes for protection, since the slopes are steep. When we got up to the higher levels, we were befuddled: we didn't know exactly where the Sun Dagger was located, or what it looked like. All we could do was look for - something, anything, out-of-the ordinary, and presumably on an exposure the sun could reach.

La Fajada Butte: from Anna Sofaer's 1979 paper in Science.

Desert regions are amazing. Vegetation is so sparse and rainfall so low, that, once disturbed by human use, the surface can reliably hold a record of disturbance for hundreds of years, if not longer. Walt and I used to laugh about it when we lived in Socorro, NM: being raised in NM, I could sense where the ancient dwellings had been in the little Piro pueblitos east of town, out towards Bursum Springs. Even as I easily located pottery shards and pulled them from the ground, Walt argued, tongue-in-cheek, that the location was perfectly natural. After a while, Walt's East-Coast-bred senses became similarly attuned to the nuances of desert vegetation and the orientation of rocks.

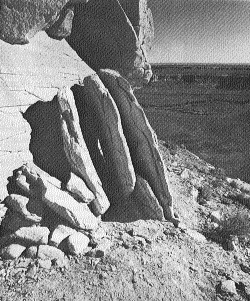

So, when we saw the rock slabs leaning against the rock wall, behind which the Sun Dagger was located, it was blindingly and immediately obvious, even from a distance, that it was manufactured. THAT was where the Sun Dagger had to be located! Rock slabs don't just prop themselves against rock walls! And, indeed, it was so! But since we had missed the solstice by about a month, and it was the middle of the day besides and were inexpert in use of the Sun Dagger, there was nothing really for us to see, except to admire the handiwork, and wonder how many people it had required to shuffle the rock slabs around - a good dozen strong people, for sure, maybe more!

Several years later, as a young graduate student, I saw a talk at the University of Arizona by another young graduate student, who was working on a theory that the Anasazi hadn't propped the rock slabs against the wall, but had instead exploited a natural location for their solstice marker. The rock slabs had fallen from above and been tilted into place by erosion from below. Presumably there weren't enough Indians available to move the rock slabs around (Chaco Canyon's central villages likely never had more than a couple of thousand or so inhabitants at any one time, although more lived in small outlying pueblitos, and religious pilgrims and traders could swell the population at times).

The rock slabs: from Anna Sofaer's 1979 paper in Science.

I was a polite student, so I remained silent, but what I needed to say to her then - what I yearn to say now - was: what complete rubbish! Rock slabs, especially fragile sandstone rock slabs, generally shatter when they fall from a height: they don't remain propped against the wall, unless the fall distance is small. And if it was a small fall distance, the location where they came from should be obvious. And it isn't! And where else in Chaco Canyon do you find rock slabs propped up against walls? Nowhere! And how could erosion easily occur behind and below the rock slabs? It doesn't rain that much, and so, unless there was a gully directly behind the slabs, you just won't have the erosive power required. And there is no gully there!

People in the modern age often make two errors when estimating the abilities of ancient peoples. First, they underestimate the determination and ability of ancient peoples in building structures. The Sun Dagger is but a modest example. Other examples abound: Stonehenge, The Pyramids.

The second error is more complicated. People derive inappropriate moral lessons from the past. In the modern environmental age, people use the shopworn storyline that ancient peoples strip the natural resources, leveling forests as they go, and are forced to move out when they exhaust what nature can provide. I'm not saying that can't happen (or will happen, say, to our civilization, like it apparently did at Easter Island), but the evidence needs to be there to make the claim. Not every situation is like that.

At Chaco Canyon, some people have said that the area was once forested, presumably in pinon-juniper forest, or - God forbid! - even in tall ponderosa pine forest! - and that the Indians systematically burned or cut the trees over the generations, until the droughts of the 1200's finally made the location unlivable, forcing the Anasazi to move to more-reliably watered locations like the Rio Grande Valley, and elsewhere.

I'm more than skeptical. Chaco Canyon's elevation just seems too low, when compared to other locations in the Southwest, for either ponderosa pines or dense pinon-juniper forest. The location is far from the mountains, and the large surface streams that flow from them, and so I doubt whether that much food was ever raised there - pocket farms in favorable locations, like the Navajo and Hopi do today, and some wild game hunting. Even in its heyday, I bet food was imported into the area. Life is tough up there on those cold plateaus! Always has been - always will be!

So the errors we need to avoid are:

- ancient peoples were incompetent; and,

- ancient peoples lived their lives to provide us with moral examples, and could single-handedly cause widespread environmental devastation.

Like us, ancient peoples were capable of amazing things, but they couldn't do everything. They were subject to the same frailties we suffer and had to obey the same laws of physics.

Here is a short list of research papers on the subject. Here is an interesting excerpt from Anna Sofaer's 1997 paper, reflecting current thinking:

Scholars have puzzled for decades over why the Chacoan culture flourished in the center of the desolate environment of the San Juan Basin. Earlier models proposed that Chaco Canyon was a political and economic center where the Chacoans administered a widespread trade and redistribution system (Judge 1989; Sebastian 1992). Recent archaeological investigations show that major buildings in Chaco Canyon were not built or used primarily for household occupation (Lekson et al. 1988). This evidence, along with the dearth of burials found in the canyon, suggests that, even at the peak of the Chacoan development, there was a low resident population. (The most recent estimates of this population range from 1,500 to 2,700 (Lekson 1991; Windes 1987). Evidence of periodic largescale breakage of vessels at key central buildings indicates, however, that Chaco Canyon may have served as a center for seasonal ceremonial visitations by great numbers of residents of the outlying communities (Judge 1984; Toll 1991).

No comments:

Post a Comment